by Aaron Kennell

February – a routine month celebrating the idyllic renaissance of a people gaining autonomy. It is also celebratory that we have elected, for a second-term, an African-American president to head the executive branch of our fabled representative democracy. How, though, do we fare on the progress of a still disenfranchised African-American people? Did our one vote, which collectively shouted with millions of voices, actually attenuate in the form of a reparations through expressing our democratic sovereignty? I would disagree.

Electing an African-American president is a significant step. However, what is missing is the consistency of our collective will to eradicate all inhumane atrocities done to this group of people. As a white male, I will not hide that I have been shielded from villainous hate and barbarous invasion of my autonomy. That goes to both my sex, gender and skin tone. I haven’t felt the lessening of my humanity through the starvation of intellect or peace of mind. My gender hasn’t been distributed and franchised in the name of patriarchy in the way a woman’s gender and identity, of all races, has been. Though there is blow back from my push towards anti-racism and feminism, I never endured the emotional and physical drain of white women and black men and women.

However, black men and women are the focus of this article and this month. I have been reminded of a memory, that has humbled me and my analysis of our democracy, since the re-election of our current President. On a November day, a Friday, I volunteered to picket in downtown Orlando, holding signs supporting hunger awareness in November (which, ironically, is mostly a month about white people and their affinity towards Thanksgiving). While roaming the streets, holding cardboard boxes as epitaphs of the decay of those who are homeless and starving, I was greeted solemnly by a homeless African-American man. The thought of giving whatever I could spare bitterly did not appear in action, and he strolled off with thanks and a strife of hope, though not towards us, but towards his condition.

After traversing further, I saw the same African-American man, unchanged in his hope in seeing our support for eradicating and illuminating his misery. We touched, hugged and cried without caring about the flavor of a post-victory celebration of the election. It dawned on me, after I had given him change for food, that I stumbled upon a dilemma.

I was the philosopher king.

He the slave to his own condition.

My mobility was unquestionably precise and without hindrance in a social setting. I remember bleakly feeling like an iconoclast in 2008 when I first elected then Senator Obama into office, discharging the idea that whiteness and white people were somehow the moral norm. Now, however, I was staring at depravity in the midst of our democracy, and how our sovereignty to vote meant nothing and changed little for the outcome of this one man, and every other woman and child facing the same fate.

What did President Obama have to say to all Americans throughout his campaign? He stated we all had to work hard. He’s right, but he never mentioned what we, as citizens, need to do for those who needed help, namely those in grave poverty, who needed the help to evolve from crawling to running in the midst of a social sea.

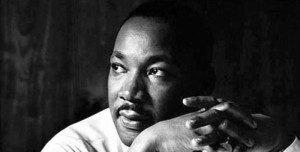

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., however, advocated a dream that every person be granted an education, to peaceably experience the dignity of their rationale, food to continue living and a general peace of mind to experience.

Should we thus realign our thoughts away from voting strictly for the sake of the democratic process, and start the dream of realizing the human (and humane) process? Dr. King would suggest the same. He would also have us recognize that we can’t put the hopes of a better nation in the hopes of one man. We were willing to cast a vote, and millions of voices were heard. It is imperative, alternatively, that we cast aside the normal passage of change, politically, and charge at the social realm of our failings; if we succeed in this endeavor, then we can claim a collective identity of the iconoclast. We need millions of hearts to be felt, and I know mine was felt that day, and my vote became less meaningful, because it did not affect the man starving of food, intellect and peace.