by Matt Isaacs, Lowell Bergman and Stephen Engelberg

This story was co-published with PBS’ “Frontline.”

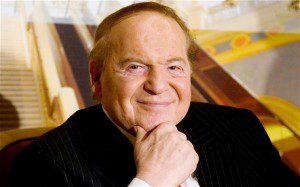

A decade ago gambling magnate and leading Republican donor Sheldon Adelson looked at a desolate spit of land in Macau and imagined a glittering strip of casinos, hotels and malls.

Where competitors saw obstacles, including Macau’s hostility to outsiders and historic links to Chinese organized crime, Adelson envisaged a chance to make billions.

Adelson pushed his chips to the center of the table, keeping his nerve even as his company teetered on the brink of bankruptcy in late 2008.

The Macau bet paid off, propelling Adelson into the ranks of the mega-rich and underwriting his role as the largest Republican donor in the 2012 campaign, providing tens of millions of dollars to Newt Gingrich, Mitt Romney and other GOP causes.

Now, some of the methods Adelson used in Macau to save his company and help build a personal fortune estimated at $25 billion have come under expanding scrutiny by federal and Nevada investigators, according to people familiar with both inquiries.

Internal email and company documents, disclosed here for the first time, show that Adelson instructed a top executive to pay about $700,000 in legal fees to Leonel Alves, a Macau legislator whose firm was serving as an outside counsel to Las Vegas Sands.

The company’s general counsel and an outside law firm warned that the arrangement could violate the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. It is unknown whether Adelson was aware of these warnings. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act bars American companies from paying foreign officials to “affect or influence any act or decision” for business gain.

Federal investigators are looking at whether the payments violate the statute because of Alves’ government and political roles in Macau, people familiar with the inquiry said. Investigators were also said to be separately examining whether the company made any other payments to officials. An email by Alves to a senior company official, disclosed by the Wall Street Journal, quotes him as saying “someone high ranking in Beijing” had offered to resolve two vexing issues — a lawsuit by a Taiwanese businessman and Las Vegas Sands’ request for permission to sell luxury apartments in Macau. Another email from Alves said the problems could be solved for a payment of $300 million. There is no evidence the offer was accepted. Both issues remain unresolved.

According to the documents, Alves met with local politicians and officials on behalf of Adelson’s company, Las Vegas Sands, to discuss several issues that complicated the company’s efforts to raise cash in 2008 and 2009.

Soon after Alves said he would apply what he termed “pressure” on local planning officials, the company prevailed on a key request, gaining permission to sell off billions of dollars of its real estate holdings in Macau.

Las Vegas Sands denies any wrongdoing. But it has told investors that it is under criminal investigation for possible violations of the U.S. anti-bribery law. Adelson declined to respond to detailed questions, including whether he was aware of the concerns about the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act when he directed payment of the bill from Alves’ law firm.

The documents depict Adelson as a hands-on manager, overseeing details of the company’s foray into Macau, which is now the world’s gambling capital.

They show that Alves helped the company address a crucial issue: Adelson’s frayed relations with officials in Macau and mainland China.

Alves met with prominent Macau officials on Las Vegas Sands’ behalf, emails show. When Adelson made a three-day trip to Beijing, Alves accompanied him, billing more than $18,000 for his services.

Alves promoted himself to Adelson as someone “uniquely situated both as counsel and legislator to ‘help’ us in Macau,” according to an email written by a Las Vegas Sands executive.

The then-general counsel of Las Vegas Sands warned that large portions of the invoices submitted by Alves in 2009 were triple what had been initially agreed and far more than could be justified by the legal work performed.

“I understand that what they are seeking is approx $700k,” the general counsel wrote to the company’s Macau executives in an email in late 2009. “If correct, that will require a lot of explaining given what our other firms are charging and given the FCPA,” the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

Adelson, described by Forbes Magazine as the largest foreign investor in China, ultimately ordered executives to pay Alves the full amount he had requested, according to an email that quotes his instructions.

Alves holds three public positions. He sits on the local legislature. He belongs to a 10-member council that advises Macau’s chief executive, the most powerful local administrator. And he’s a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a group that advises China’s central government.

Alves did not respond to detailed questions from reporters about his activities on behalf of Las Vegas Sands, saying in an email that the work he had done — “legal services” — was unrelated to his government positions. “I would never use my public offices to benefit the company, nor have I been asked to,” Alves wrote.

Several Las Vegas Sands executives resigned or were fired after expressing concerns about Alves’ billings. These include Las Vegas Sands’ general counsel and two top executives at Sands China, its Macau subsidiary.

Alves briefly severed his relationship with the company in early 2010, according to internal documents, but was rehired months later as outside counsel, a role he still plays.

The internal Las Vegas Sands documents were obtained by reporters working for the University of California’s Investigative Reporting Program as part of an ongoing collaboration with ProPublica and PBS Frontline.

The documents include dozens of emails, billing invoices, memos and reports that circulated among top executives of Las Vegas Sands and its attorneys. The documents were provided by people who had authorized access to them. They offer important glimpses of the company’s dealings in Macau and China, but are not a complete archive.

One invoice, for example, notes that Alves billed $25,000 for “expenses” in Beijing with no further explanation.

The documents shed new light on an issue separate from Alves’ work: the company’s difficulties in avoiding contact with Chinese organized crime figures as it built its casino business in Macau.

Nevada law bars licensed casino operators from associating with members of organized crime. State investigators are now assessing whether Las Vegas Sands complied with that rule in its Macau operations, people familiar with the inquiry said.

William Weidner, president of Las Vegas Sands from 1995 to 2009, said he understood from the beginning that opening casinos in Macau meant dealing with “junkets” — companies that arrange gambling trips for high rollers.

Gambling is illegal in mainland China, as is the transfer of large sums of money to Macau. The junkets solve those problems, providing billions of dollars in credit to gamblers. When necessary, they collect gambling debts, a critical function since China’s courts are not permitted to force losers to pay up.

Weidner said junkets are a natural result of China’s controls on the movement of money out of the country, channeling as much as $3 billion a month from the mainland to Macau.

“To Westerners, the junkets mean money laundering equated with organized crime or drugs,” he said. “In China where money is controlled, it’s part of doing business.”

Weidner resigned from the company after a bitter dispute with Adelson.

Nevada officials are now poring over records of transactions between junkets, Las Vegas Sands and other casinos licensed by the state, people familiar with the inquiry say. Among the junket companies under scrutiny is a concern that records show was financed by Cheung Chi Tai, a Hong Kong businessman.

Cheung was named in a 1992 U.S. Senate report as a leader of a Chinese organized crime gang, or triad. A casino in Macau owned by Las Vegas Sands granted tens of millions of dollars in credit to a junket backed by Cheung, documents show. Cheung did not respond to requests for comment.

Another document says that a Las Vegas Sands subsidiary did business with Charles Heung, a well-known Hong Kong film producer who was identified as an office holder in the Sun Yee On triad in the same 1992 Senate report. Heung, who has repeatedly denied any involvement in organized crime, did not return phone calls.

Allegations about the company’s dealings with Alves as well as its purported ties to organized crime are prominently mentioned in a 2010 lawsuit filed by Steven Jacobs, former CEO of Sands China.

In the suit, Jacobs contends he was fired after multiple disputes with Adelson, which included the continued employment of Alves and the company’s dealings with junkets.

Las Vegas Sands declined to respond to detailed questions about the emails, billing invoices or purported relationships with organized crime figures including Cheung and Heung. Nor would it comment on the federal or Nevada investigations.

Adelson told investors last year that the federal investigation was based on false allegations by disgruntled former employees attempting to blackmail his company.

“When the smoke clears, I am absolutely not 100 percent but 1,000 percent positive that there won’t be any fire below it,” he said, adding that what investigators will ultimately find “is a foundation of lies and fabrications.”

At least one prominent Republican has expressed concern about the source of Adelson’s campaign contributions. “Much of Mr. Adelson’s casino profits that go to him come from his casino in Macau,” Sen. John McCain noted in an interview last month with the PBS “NewsHour.”

“Maybe in a roundabout way, foreign money is coming into an American political campaign,” said McCain, an Arizona Republican.

The questions raised by McCain and others have not prevented Adelson, the self-made son of a Boston cabdriver, from emerging as a powerful political figure in both Israel and the United States. A longtime backer of Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu of Israel, Adelson created a free daily newspaper, now Israel’s largest, that supports the policies of Netanyahu’s Likud Party.

His family’s $25 million in contributions kept Newt Gingrich in the presidential race. He has been widely reported as donating $10 million to a super PAC supporting Mitt Romney. A “well-placed source” recently told Forbes Magazine that Adelson’s willingness to financially support Romney was “limitless.” A filing with the Federal Election Commission last night shows that Adelson and his wife, Miriam, gave $5 million to the “YG Action Fund,” a super PAC linked to House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, a Virginia Republican.

***

Macau’s emergence in the 21st century as the biggest gambling center in the world, with $33.5 billion in annual revenue — four times that of Las Vegas — is a matter of history and geography.

A former Portuguese colony, the tiny peninsula was handed over to China in 1999. It has its own legislature, laws, court system and chief executive, all of which exist under the umbrella of Chinese control.

For generations, profits from Chinese gambling flowed primarily to a single local company. But after China took control, authorities agreed to let foreign companies get a piece of the action.

Las Vegas Sands was among more than a dozen companies to apply for a license. Its plans were among the most expansive, calling for an American-style complex of hotels, casinos, shopping malls and luxury apartments.

The first of four Las Vegas Sands casinos, the Sands Macau, opened its doors in 2004. It was immediately successful as well-heeled gamblers from the mainland flocked to the tables.

Over the next several years, the company pushed ahead with its multibillion-dollar construction projects on a strip of reclaimed land known as Cotai.

But in the summer of 2008, Las Vegas Sands faced a cash crunch. The global economic slowdown hit revenues at its casinos in Nevada. And gambling slowed in Macau after China’s central government abruptly cut down on the number of visas it granted for travel to the region. Suddenly, the company was struggling to make payments on billions of dollars in long-term debt.

Executives at Las Vegas Sands began looking at ways to raise cash in Macau. To do this, the company would need some help from local officials.

It wasn’t clear they would get it.

In China, relationships, or guanxi, can make or break an empire. Adelson’s relationships in Macau and China were frayed. George Koo, a member of the Las Vegas Sands board of directors, wrote in a confidential memo that Adelson’s behavior had offended political figures in both Macau and China.

Koo quoted a prominent Macau official as saying Adelson had “slapped the table in front of Edmund Ho,” Macau’s chief executive. “Supposedly, Ho has said that he will not see SGA anymore,” the memo said, using Adelson’s initials.

Accompanied by Alves, Koo met with the Macau chief executive over lunch. According to Koo’s memo, Ho expressed his regret that Adelson “has burned so many bridges with Beijing,” the memo said.

According to Koo’s account, a top Chinese official overseeing Macau named Liao Hui was so angry at Adelson that he refused to meet with him. It is not clear from the memo what caused the rupture, but Koo said Adelson turned to “the Israeli military to arrange a meeting with Liao” who initially agreed but then said he would only send his deputy. No meeting ever took place, the document says.

Weidner, who resigned as president of Las Vegas Sands in March 2009, said in an interview that Adelson was “out of his element” dealing with Chinese officials.

Weidner recalled struggling to explain Adelson’s style to the Chinese, once comparing his boss to a famous emperor who became angry with China’s scholars and buried them alive with their books. “I would tell them: ‘He is brilliant. Sometimes, like the emperor, he is brutal.'”

Leonel Alves seemed to be an ideal person to smooth relations.

A Macau native, born of a Portuguese father and a Chinese mother, the attorney had been a fixture in the local scene for decades, and was nimble in the face of shifting political tides.

In the years leading up to Portugal’s handover of its onetime colony to China in 1999, he was among a select group of local residents chosen to serve on the transition team.

Alves became a Chinese citizen and dedicated himself to learning China’s official dialect, Mandarin, to complement his fluency in Portuguese, English and Cantonese. His legal practice was already successful. He boasted to local reporters of his car collection, which included a Ferrari and a BMW M3.

Las Vegas Sands put Alves’ law firm on retainer in midsummer 2008, naming him as an outside counsel. Documents show his firm was to be paid $37,500 a month for 80 hours of work, with additional hours to be billed at a rate of more than $550 an hour.

Over the years, the Justice Department has made it clear that American companies can employ foreign officials. But companies have been told they must take great care and create safeguards to prevent such officials from using their position or political standing to gain commercial advantage.

T. Markus Funk, a partner at the Perkins Coie law firm and co-chair of the American Bar Association Global Anti-Corruption Initiatives Task Force, declined to discuss the specifics of the Las Vegas Sands inquiry. But he said companies generally avoid hiring sitting local officials as lobbyists or representatives because of the risk that they will improperly end up wielding their influence.

“It would be a huge red flag,” said Funk. “If you are paying someone because you think they are going to have a questionable backroom discussion, essentially a quid pro quo relationship, that’s a no-no. You can get yourself in big trouble pretty quickly.”

In response to written questions, Alves said in an email that his political career has never conflicted with “my profession as a lawyer.” He said his office had “been scrutinized by the Chinese and American authorities like few have in Macau, and no authority has ever had any suspicion.”

Alves noted that his multiple government posts did not “confer to me any executive and administrative power” or the ability to “influence” what he described as “the relevant authorities.”

U.S. companies sometimes ask the Justice Department in advance for an opinion on whether a particular hire constitutes a violation of the law. It is not known if Las Vegas Sands posed such a question about Alves. Funk, a former federal prosecutor, said that a company following “best practices” would look closely at both the size of the proposed payments and the procedures put in place to assure compliance.

“I’d want to make sure the individual is getting paid an appropriate scale,” Funk said. “I’d want to get some assurance he was familiar with the FCPA and had agreed to abide by its terms. I’d want a code of conduct in place and I’d want to see detailed billing statements.”

One of the first issues Alves addressed was Las Vegas Sands’ request for permission from local authorities to sell a mall and 300 luxury apartments it had built next to one of its casinos, the Four Seasons Macau.

The company’s original agreement with the government did not allow it to break up the property into separate pieces for sale. If Sands could amend the agreement, it would open the way to raise billions.

On Aug. 12, 2008, Alves wrote an email to Luis Melo, who was then Las Vegas Sands’ in-house counsel in Macau. He wrote that he was planning to meet with local officials to “monitor and apply pressure” to what he called the “revision process” of the “land concession contract.” It is not known whether the meeting took place or what, if anything, Alves said to other officials in the government.

In late September, the secretary of Macau’s Land, Public Works and Transport Bureau declared that Las Vegas Sands had to abide by its original contract with Macau, which did not permit the property to be sold separately.

“The terms in the concession contract are very clear and any move must be according to what is written in the contract,” he said, according to a report in The Macau Daily Times.

That statement came at a critical moment for Las Vegas Sands. With the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the United States, even the most solvent companies were finding it impossible to borrow. At the end of September, Adelson staked his company $475 million of his own money.

In October, planning officials handed Las Vegas Sands much of what it was seeking. They said they would allow the property to be divided into four parts: the casino, the apartment complex, the mall and a parking garage. Each could be sold separately. In their decision, Macau officials said they were trying to help Las Vegas Sands address its need for more capital.

The company portrayed the decision as a victory and said it “paves the way” for the sale of the 300 luxury apartments.

The company’s financial condition continued to worsen. It halted construction on its massive projects in Cotai. In November 2008, Adelson kicked in another $525 million of his own money. That month, the company told investors it was in danger of defaulting on $5.2 billion in loans. Such a default, auditors warned, could threaten the company’s survival.

Ultimately, Las Vegas Sands did not sell the apartment building or mall. (It continues to seek final permission to sell individual apartments.) The company moved to raise capital through another route: an initial public offering of stock on the Hong Kong exchange that, it was hoped, would bring in billions of dollars.

Once again, local law posed challenges to the company’s plans. And once again, Alves stepped forward to help.

* * *

One key to Las Vegas Sands’ survival in Macau was its ability to whisk customers from Hong Kong to the doors of its casinos. The long-established ferry route unloads its passengers in downtown Macau, about a three-mile drive from Adelson’s casinos in Cotai.

Las Vegas Sands had created its own ferry service, Cotai Waterjets, which dropped gamblers at a dock just a short shuttle ride from its casinos.

But the future of Cotai Waterjets was unclear. A competing ferry service had filed a complaint alleging the government had improperly awarded the concession to Las Vegas Sands without competitive bidding.

In February 2009, a Macau court agreed, voiding the contract.

Alves set to work. In the spring of 2009, he arranged what a billing invoice from his firm describes as “meetings and contacts with the Macau Government.”

On Oct. 19, 2009, Alves met with Edmund Ho, Macau’s chief executive, and Fernando Chui Sai On, Ho’s soon-to-be successor. (Ho was the Macau official who had purportedly refused to meet with Adelson.)

It is not known what was discussed. Alves billed Las Vegas Sands for two hours of his time, according to his invoice.

Also that day, Alves billed for more than an hour of phone calls with company executives, his invoices show.

Las Vegas Sands was explicit about what was at stake, telling Hong Kong investors in a public filing that loss of the ferry concession “could result in a significant loss of visitors to our Cotai Strip properties.” This would have a “material adverse effect on our business,” the company said.

Within days of Alves’ meeting with Ho, Las Vegas Sands won a stunning victory. Ho issued an administrative regulation that allowed ferry contracts to be awarded without competitive bidding. The court rulings against the company were moot. Las Vegas Sands retained control of its route and ultimately obtained several new ones.

Attempts to reach Ho were unsuccessful.

The initial public offering launched in late November 2009, raising $2.5 billion for Las Vegas Sands.

Alves remains a member of the Executive Council. He declined to discuss his interactions with Ho or the council.

* * *

Just as Sands was resolving several of its thornier legal issues, a dispute erupted among its executives over Alves that had far-reaching consequences.

It began on Oct. 20, 2009, shortly before the ferry decision was announced, with a seemingly routine event: Alves’ firm submitted bills for its recent work.

The firm said it was charging at triple the previously agreed rate to account for the work it had done on the public offering, scheduled for the following month. In an email, Las Vegas Sands’ in-house lawyer in Macau, Luis Melo, objected, noting the invoices were“not in accordance” with the letter which spelled out the financial terms of Alves’ retainer.

The issue reached the desk of J. Alberto Gonzalez-Pita, general counsel at Las Vegas Sands headquarters in Nevada. In an email, Gonzalez-Pita expressed concern about a sudden request for more money from an outside lawyer who was also a foreign official, saying such a payment would require “a lot of explaining.”

With the bill still unpaid, Alves submitted his resignation effective in February 2010.

An internal email shows he continued to report privately to Adelson, delivering at least one message from the company’s chairman and CEO to Macau’s government.

Separately, he also pushed to return to Sands China.

In March, Alves submitted a new proposal, asking to be paid $125,000 a month with no obligation to provide billing details, internal records show.

Gonzalez-Pita, the Las Vegas general counsel, rejected the idea. “It’s outrageous,” he wrote. “Our corporate retainer with Paul Weiss is almost three times less per month,” he said, referring to the company’s outside counsel, New York-based Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison.

Gonzalez-Pita elaborated a week later.

“I continue to believe this proposal to be inappropriate, unrealistic, extraordinarily expensive and way above market,” he wrote to Jacobs, the CEO of Sands China who had originally been recruited to handle the IPO. “Been a long time since I’ve seen a lawyer or a firm make as naked a power play as has LA,” Leonel Alves. “He sure has chutzpah.”

Jacobs decided against rehiring Alves. “Let’s talk about a replacement for outside counsel,” he wrote in a March 10, 2010, email to Melo, Sands China’s general counsel in Macau.

“The transition will not be easy … and has a high probability of becoming messy … but it is the right thing to do for the business,” he wrote.

Jacobs told Alves that he would not be retained, emails show.

The same day, Jacobs informed colleagues that he had paid the disputed invoices after Alves submitted a more detailed account of the work he had done on the public offering. Jacobs wrote to Gonzalez-Pita that he had been “instructed by SGA and MAL to pay and close out the matter.”

The initials SGA and MAL are used within the company to refer to Sheldon G. Adelson and Michael A. Leven, the president of Las Vegas Sands.

“I am sorry that this was not communicated to you but I am glad that FCPA outside counsel did not highlight any substantial issue with the payment,” Jacobs wrote.

Gonzalez-Pita replied that Jacobs was mistaken and that the company’s outside lawyer had identified the payments as a possible violation of the U.S. anti-bribery law.

“Unfortunately,” Gonzalez-Pita wrote to Jacobs: “FCPA counsel did highlight a problem” with paying Alves anything more than his normal fees “plus a commercially reasonable premium.”

“While I can appreciate that you received instructions to make the payment,” Gonzalez-Pita wrote on March 12. “I wish you would have advised me so I could have intervened.”

Gonzalez-Pita resigned from the company in April 2010.

On July 23, Las Vegas Sands fired Jacobs. A month later, the company dismissed Melo and the rest of the legal team in Macau, according to the lawsuit Jacobs subsequently filed in Nevada.

In that action, Jacobs said he was dismissed for refusing Adelson’s “illegal demands,” including an order that he fire Melo and replace him with Alves. Las Vegas Sands said in court briefs that it fired Jacobs for disobeying orders and working on unauthorized deals.

The company rehired Alves as outside counsel in the fall of 2010, a position he still holds. It is not known how much he is being paid.

In April of this year, Sands China opened Cotai Central, the $4 billion project it had temporarily abandoned in 2008, when the company stood at the brink. Within six hours of the opening, Sands China reported, more than 84,000 people pushed through the new casino’s doors.

Matt Isaacs and Lowell Bergman reported on this story for the Investigative Reporting Program of the University of California and PBS Frontline. Some of their work was underwritten by a grant from the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Engelberg is managing editor of ProPublica.