Florida ranked 43rd of the 50 states for homeless kids, according to a 2006 study

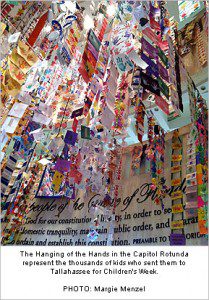

It’s Children’s Week at the Capitol, marked by thousands of colorful hand cut-outs hanging down the open floors of the rotunda. The man behind the yearly spectacle – Ted Granger, executive director of the United Way of Florida – is gearing up for a make-or-break week on bills that could help kids.

“Florida’s children today are struggling,” he said. “We’re still coming out of the Great Recession. We’re in a moribund economy.”

By Granger’s figures, the recession lasted twice as long — 20 months — and cost twice as much — 4 percent of GDP — as other U.S. recessions since World War II. Now, although the economy is starting up again for many Floridians, others are still hurting.

One in five Florida families reported there were times last year when they didn’t have money for food. Bottom line: 19.2 percent of adults and 28.4 percent of children are sometimes hungry in Florida, compared to national averages of 16.1 percent for adults and 21.6 percent for children.

The Rev. Pam Cahoon is executive director of CROS (Christians Reaching Out to Society) Ministries, a coalition of about 100 religious groups that runs food pantries and other programs to feed the hungry in Palm Beach County. One is an after-school snack program that CROS took over from a city program that couldn’t afford it anymore.

Cahoon said kids in the free- and reduced-price lunch program often eat their lunches by mid-morning.

“There were just a lot of discipline problems, and so we started getting groups to provide sandwiches for the kids after school — and the discipline problems went away,” Cahoon said. “Those kids were just hungry.”

CROS also started sending backpacks of food home for the weekend, because teachers were seeing students come in hungry on Monday morning. Academic performances improved.

“Principals have identified the children we’re giving the backpacks to,” said Cahoon. “It’s the kids that go around the cafeteria and say, ‘Are you not going to eat that apple? Are you not going to eat that orange — may I have it?’ It’s the child that lays their head on the desk because they’re hungry, and they can’t keep their head up and do their schoolwork.”

POVERTY AND HOMELESSNESS

A 2006 report, America’s Youngest Outcasts: State Report Card on Child Homelessness, ranked Florida 43rd of the 50 states for homeless kids. At the time — during the 2005-2006 school year, before the recession — 49,886 children and youths were homeless in Florida. By 2008-2009, that number had grown to 70,633 — a 42 percent increase in three years.

The economic downturn has led to increases in numbers of homeless children and families. Most of these children are not living on the streets, but with their families in shelters, substandard housing or doubled-up in unhealthy situations.

About 21 percent of Florida children were living below the federal poverty level in 2009, according to U.S. Census data. A disproportionate number of children were black (38 percent) or Hispanic (25 percent) compared to white children living in poverty (12 percent).

Then there are children who become homeless because the alternative is worse. Last year about 7,500 Florida children fled violent homes with a parent, said Leisa Wiseman of the Florida Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

Florida battered-women’s shelters housed about 15,000 people in the last fiscal year, and 7,484 were children under the age of 18.

“When they’re in shelter, they’re safe,” Wiseman said. “They’re receiving services, with the mom, that they need.”

But again, because of the recession and the lack of affordable housing, Florida’s domestic violence shelters were forced to turn away 3,471 requests for emergency shelter in 2012.

“It’s disruptive, there’s no doubt,” Wiseman said. “They may have to change schools because of safety. The perpetrator may know where to find that child at school.”

Granger said because there hasn’t been a budget surplus since before the recession, lawmakers will have a tough job sorting out everyone’s needs. There are potholes and crumbling infrastructure everywhere you look, he said.

“But from our point of view, the most important infrastructure is the human infrastructure,” he said. “If we don’t have a solid human structure, everything else doesn’t matter.”

Granger, Cahoon and other children’s advocates will visit lawmakers this week with that message.

Senate President Don Gaetz, R-Niceville, is already on board. He praises programs like Cahoon’s, but is also asking both the Senate and House to boost funding for food banks and homeless programs.

“We want to make sure the money is used properly,” he said. “But I think those are areas where even the most conservative Republican — and I’m a conservative, and I’m a fiscal conservative — that the most vulnerable folks in our society — the disabled, children, and hungry and homeless people — are the very people we ought to be helping.”

by Margie Menzel