Compared to most people, Judi Hayes has critical thinking skills more honed than most. A litigation attorney by training, she set her legal career aside for several years to focus on family. Her sons, Jack and Will, are going into seventh and third grades respectively, at their local public school they have attended for years. Despite Hayes’s ability to think through complex problems, she is still undecided as to exactly how her two sons will continue their education next month. Like many parents, she is concerned with the COVID-19 pandemic and does not think spending six or seven hours a day in classrooms will be conductive to their health—or their development. Although resigned to avoid physical classrooms for now, Hayes is looking forward to hearing the details of the school re-opening plan, to be voted on by the Orange County School Board next week.

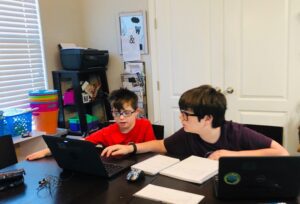

Hayes has promoted the idea of a combination model for her sons’ learning. A combination model would avoid some of the problems with a strict, 100% online model. “No kid is going to sit in front of a computer for six hours straight,” she concedes while describing the best options she has heard of, which include a combination of options. The combination model would work well for her oldest son, who is gifted, Hayes says. However, she has concerns for her youngest, who has been diagnosed with Down Syndrome and needs regular support from a variety of special education providers. Will’s need for occupational therapy, physical therapy, and the support of a Speech Language Pathologist has weighed on Hayes’s mind constantly since schools closed, statewide, in March.

The new school year brings higher numbers of positive COVID-19 cases, with Florida measuring record high number of cases and deaths over the past few weeks. The new school year also brings with it the opportunity to work with new teachers and support personnel, Hayes says. Although the school where her sons go to school has been supportive, Hayes worries that remote learning is not a sufficient replacement for them. Hayes recognizes that, despite her sons’ needs, the schools re-opening present a tremendous number of difficulties.

“I’m surprised an injunction hasn’t already been filed on behalf of the school employees,” she declares with exasperation. Hayes says that, “the most insurmountable barriers for schools to re-open are the employment issues.” “If I were John Morgan, I would simply be waiting for the phone to ring,” she adds.

Although Hayes had gone back to work this past school year in November, she set her legal career aside again in March with the school closures. She acknowledges that her family is afforded the, “luxury,” that they can make ends meet on her husband’s salary, who is also an attorney. With uncertainties because of the coronavirus pandemic, she does not see herself arguing cases again anytime soon. She is quick to compliment the many teachers, principals, and district employees who have helped her sons progress academically and developmentally. She also offers that ultimately, “everyone is better off in the classroom,” even if classrooms are not a safe option for the time being.

For now, there are no easy answers for the Hayes family. Although the OCPS School Board is expected to vote on a school re-opening plan next week, the Devil might be in the details. Hayes’s family had a, “major re-calibration,” when schools were closed and she stopped her work as a litigator. The major re-calibration that Hayes and hundreds of thousands of families across Florida had to endure came after state officials closed schools in March due to coronavirus spreading. An emergency order dated July 6 from Education Commissioner Richard Corcoran requires schools to re-open with complete education services in August. Hayes was “surprised,” by the Commissioner’s order to require schools to re-open, promulgated only one day before Governor DeSantis extended the statewide state of emergency by sixty days. “They are not taking our kids safety into account,” she offers with frustration. Despite her worries that her sons will lose the progress they have made, she says her sons are, “likely not going on campus anytime soon.”

This article is one in a series of articles about school employees and public health.