“28 Negros to Mix Schools Here”

“Orlando’s record of good race relations is second to none.”

This is the sixth in a series of articles focusing on the momentous local changes and events in the civil rights struggle, fifty years ago in Orlando, by Doug Head, former Orange County Democratic Party Chair.

In early August 1963, Orlando, and the nation, were caught up in a strange vortex of conflicting and swirling currents of change. It’s hard to over-estimate the overlapping impact of changes in race relations, the public fear of Communism, Supreme Court cases banning public prayer in schools, and the impending March on Washington, scheduled for the 28th of August. The likes of it had never been seen. All of these currents were manifest in the strange silence that settled over Orlando in early August as the City closed all its pools and recreational facilities to prevent racial clash for the last weeks of the summer.

Orange Schools, like those in all of Florida were now teaching a new course (the first such mandate in the nation of any prescribed curriculum) “Americanism vs. Communism,” which portrayed the evils of Communism and the benefits of Capitalism (labeled “Americanism”). Angry letters to the editor proposed constitutional amendments to overturn the ban on publicly led prayer in the schools. And Mayor Carr told the public that Orlando’s pools and libraries would NOT be available to County residents unless County Commissioners coughed up some money.

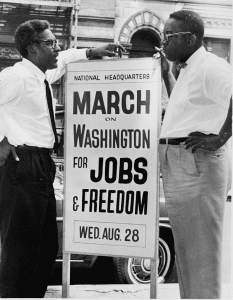

But the big anticipated event was the March, initiated by A. Phillip Randolph, the Black trade unionist. The Sentinel reported that in Hollywood, Tony Curtis, Marlon Brando, Burt Lancaster and Charlton Heston had met at Heston’s house to announce: “We will march,” they said, “because we recognize the events of the Summer of 1963 as among the most significant we have lived through.” They wanted to be part of fulfilling century-old promises, they said. Randolph summed up the point of the March and the fear of the Congressional deliberations about civil rights laws, “Once we go inside [the halls of Congress] we are licked. So we will keep our people out on the streets all summer and all fall and, if need be, all winter.” Southern Congressmen said the March was “Communist dominated.” Harry Belafonte was going and so was UAW President Walter Reuther; they planned to see President Kennedy. The Sentinel ran a cartoon showing a baseball-uniformed “Kid Kennedy” tossing up a fused bomb labeled “Racial Demonstrations” as the public scattered for cover.

A side-bar story for much of the County was significant for Orlando, with its giant Air Force Base south of town, ready for a scrap with Cuba. Defense Secretary McNamara infuriated Mississippi Senator Eastland when he ordered base commanders to declare businesses and communities off limits if the practiced “relentless discrimination” against Negro servicemen continued. Eastland said McNamara was “perverting” the mission of the armed forces. A South Carolina Congressman said, “This is the beginning of a police state and commissar government in the United States.” Another Sentinel cartoon showed an angry Democratic Donkey (“Anti-Kennedy feeling in the South”) with a nervous LBJ ordered by Kennedy to tame the beast.

The Negro Edition of the Sentinel reported success with Negro recreation programs culminating in city-wide ping pong, wheelbarrow and sack races and jacks and kickball. Though the pools were closed city-wide, the Sentinel printed old pictures of Negro swimmers at the Negro pool, from earlier in the season. In nearby Ocala, kids picketing in downtown were arrested (for their own safety said the police), then released, and adults in that community planned boycotts of shops.

One clear sign of progress to come was the decision by the School Board, as reported to the Republican Party meeting, to issue bonds to pay for new schools. They were planning for double sessions at practically all public schools. A proposed Negro Richmond Heights school was put on hold while money went to overcrowded White schools. Carver School was forced to afternoon sessions at Jones. The planners were clearly thinking about the future, by building schools in many places. Memorial went on the drawing boards and nobody was fooled about its destiny. We can’t “fall short of our contribution to civilization,” said the School Board members. The Board incurred the wrath of Elections Supervisor Dixie Barber and the County Commission as the vote required a new registration of property holders who could vote, and a clean-up of the rolls to get a majority. Many new Black homeowners were in this new group and their votes were needed.

And on August 7th, the Sentinel front page offered a new number. “28 Negros Slated to Mix Schools Here” said the headline. Superintendent Kipp knew what the McNamara order meant; Orlando would have to be tolerant with military families. Suddenly he advised that twenty Black kids were enrolled at Durrance Elementary and three at Oak Ridge High, near the air base. Including the previously announced solitary Negro at Winter Park High, five other children would also attend White schools in Orange County, he said. School had not started, but people were nervous enough for this to be news.

The Sentinel Cartoon showed Kennedy writing on a document labeled “Welcome to Washington Racial Demonstrations” Speech as Chicago, New York, Detroit and Boston exploded behind him. A letter writer to the Sentinel angrily denounced JFK, who “sent troops into Mississippi and Alabama, but let the Reds into Cuba.” Another, perhaps of more note, after denouncing the Kennedy program, reported, “the colored people of Orlando are the best behaved, most well-mannered I’ve come across” and the Editor responded, “Orlando’s record of good race relations is second to none.” The same paper reported “Reds Trying to Infiltrate Negro Civil Rights Groups.”

The estimates of the Washington March attendance now exceeded 250,000 and the Florida NAACP announced a planning meeting and “staging areas” for the trip in Orlando. On 15th August, the Sentinel Cartoon showed a nervous sweating Kennedy offering a key to the City of Washington to a gigantic thug trailing wreckage labeled “Racial Demonstration – August 28th.” “You’re going to be a good boy, aren’t you?,” says the cartoon Kennedy. Clearly, the Sentinel Editor was worrying. What would happen if Orlando’s “well-mannered Negros” acted? There were still two weeks before the event and the schools were not yet open.

Sixth in a series of articles on Orlando civil rights struggle.